Value-Based Care Five Key Competencies for Success

This white paper reviews the stages of value-based contracting, including the difficult lessons learned by early clinically integrated systems, the new dynamics that drive VBC success, and the key interventions that impact contracts. The paper also explains how, by leveraging a framework based on a thorough understanding of five population health management (PHM) competencies, health systems can drive effective clinical and financial outcomes across the value-based care continuum.

Introduction

U.S. officials have made it clear that they will continue to link healthcare payments to value-based care. It is expected that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) wants all providers to take some downside financial risk by 2025. The U.S. government also wants half of Medicaid and commercial payer contracts to follow value-based care models by 2025.1 After slow adoption of the government’s alternative payment models (APMs), the COVID-19 pandemic has brought changes to healthcare that will impact us for years to come, specifically stimulating the growth and success of value-based care (VBC). From telehealth to care management – healthcare delivery changed rapidly in response to the pandemic. Many health systems learned that reliance on traditional fee-for-service (FFS) left them vulnerable to dramatic financial volatility and drastic shifts in volume and demand. This realization that there is risk in FFS has made VBC payments a more stable form of reimbursement.

With FFS volatility and proven success in APM opportunities, such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), organizations can no longer afford to sit on the sidelines of payment transformation. According to the 6th Annual Numerof State of Population Health Survey2 of 300 healthcare leaders, 80% of respondents said that population health would be “very” or “critically” important going forward with 31-35% of their revenues coming from VBC contracts with either upside gain and/or downside risk in the next two years. The biggest factors cited for for slowing VBC adoption from this report are the threat of financial losses and the difficulty of changing organizational culture.

This white paper reviews the stages of value-based contracting, including the difficult lessons learned by early clinically integrated systems, the new dynamics that drive VBC success, and the key interventions that impact contracts. The paper also explains how, by leveraging a framework based on a thorough understanding of five population health management (PHM) competencies, health systems can drive effective clinical and financial outcomes across the value-based care continuum.

Defining the Value-Based Care Continuum

While the term “value-based care” was coined in 2006, the concept of reimbursing physicians based on the quality of the care they provide rather than the number of services provided has been very slow to be implemented.

The first meaningful step towards a payment model that was based on value rather than services came under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) when CMS released the first applications for the MSSP3 , providing a mechanism for healthcare providers to work together to deliver high quality care at a lower cost.

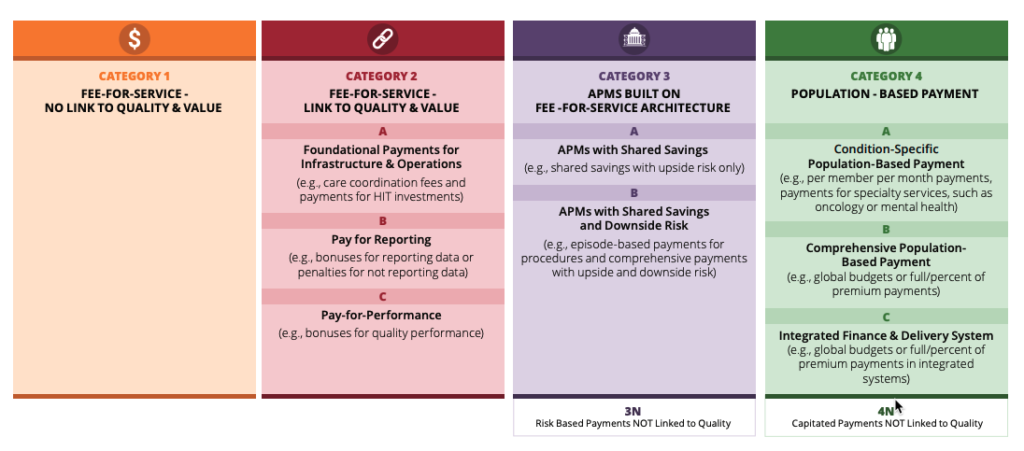

From there, the Healthcare Payment and Learning Action Network (HCP-LAN), a group of public, private, and non-profit organizations devoted to spreading VBC initiatives, built a framework and defined APMs on a continuum. Figure 1 shows these definitions from category one (fee-for-service) to category four (population-based payment). In building the APM framework, HCP-LAN authors agreed that the objective of payment reform was to change national trends and move payments into categories three (APMs built on fee-for-service architecture) and four (population-based payment), per Figure 1.

Organizations operating under VBC payment arrangements have come a long way since the first Accountable Care Organizations were formed, but several challenges are still slowing the transition to a true value-based payment model for many organizations including:

- Threat of financial losses

- Cultural resistance to a new reimbursement model

- Changing regulatory requirements

- Interoperability and data aggregations challenges

To succeed in at-risk contracts organizations will need to be able to access and analyze data across their clinically integrated organizations. They must continuously review and optimize the five core PHM competencies through a continual review and improvement process.

Figure 1: The payment model framework, from fee-for-service to population-based payment

Optimizing the Five Key Competencies

To achieve PHM transformation, organizations must create a governance structure that uses an effective framework based on five competencies:

Competency #1: Governance that Educates, Engages, and Energizes

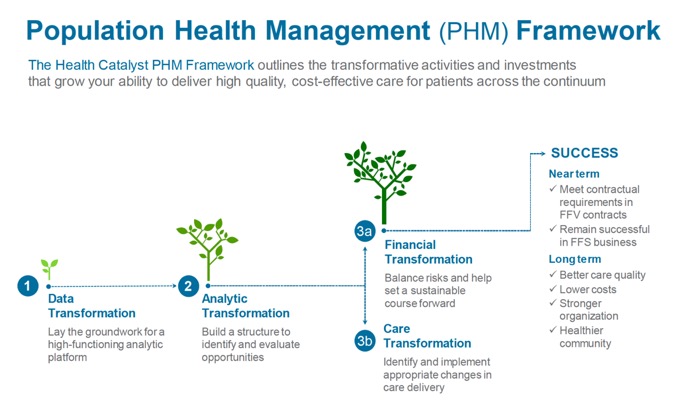

Figure 2 shows Health Catalyst’s framework for PHM success, from data and analytic transformation to payment and care transformation. A preliminary step to this framework is identifying organization-wide governance that will oversee the transformation to VBC. A governance process that educates, engages, and energizes clinicians and stakeholders is a critical step in building a strong culture that can support difficult financial, clinical, and patient-focused decisions over the long-term.

As organizations establish governance, they typically form committees with charters that include authority and responsibility, definitions of success, and participation standards. This is a critical step, as many operational teams will work together for the first time, and/or in new roles, in VBC transformation—often to impact metrics that are new to them.

A fast track to success in this step is bringing the right people into the operational teams. In general, clinically integrated organizations seek lean teams that can impact interventions. Several roles are critical for engaging executives and spreading quality and cost reduction initiatives:

- Data stewards and data analysts. These distinct resources need to interact with the right data (claims, clinical, and financial) and disseminate that information to the right end users, including leadership and frontline clinicians. Data stewards control the data, while data analysts identify intelligence in it.

- Care management leaders. Whatever form of care management clinical intervention the organization takes, it must have a leader who facilitates programmatic goals while interfacing with executive leaders.

- Project management resources. Many clinically integrated entities and ACOs spend substantial dollars on individuals trained in provider support services. These individuals work with multiple clinics to manage deadlines and facilitate success on key contract elements, such as hierarchical coding category (HCC) documentation, patient/physician usage (sometimes known as leakage), and weekly clinical huddles.

- Cross-departmental facilitator. This jack-of-all-trades role helps coordinate organization-wide contract-based elements. For example, the facilitator may lead a cross-departmental effort to incorporate non-billable CPT-II quality tracking codes for data when submitting billable data. These codes have become increasingly popular to help clinical teams capture completed work supporting the claims-based quality measures in Medicare payment models.

Figure 2: A PHM framework for transformation

Competency #2: Data Transformation that Addresses Clinical, Financial, and Operational Questions

As the governance structure evolves, organizations must take a data-driven approach to answer clinical, financial, and operational questions. To gather insights over time, health systems must identify a variety of sources that can produce intelligence and drive interventions across the clinically integrated entity’s needs. These interventions should not wholly depend on claims data.

For example, organizations often use cost movement – achieving lower total cost of care across a population by shifting the costs to a less-intensive resource – as an initial intervention based on available data. To meaningfully reduce costs, claims data needs to be integrated with additional sources. Today’s clinically integrated organizations have begun using additional data sources to identify interventions that impact the actual costs necessary to deliver care to their patients.

Organizations drive intelligence by ingesting the following data:

- Claims data. Claims data provides a phenomenal view across the continuum of a patient population, allowing organizations to see patient utilization in care delivery areas not previously visible.

- Clinical data. Connecting claims data with the right clinical data (e.g., daily patient statistics and admit-discharge-transfer feeds) from multiple settings provides accurate patient-specific data. To effectively impact cost reduction opportunities, clinical leads and care management teams need as close as possible to real-time patient lists describing patients at-risk for inpatient, readmission, or high-cost scenarios.

- Costing data. In addition to claims and clinical data, costing data is the third leg of the data stool. Many value-based contracts rely on reviewing key utilization statistics and per member per month (PMPM) spend. Knowing the actual cost to produce the care delivered, however, remains an undervalued endeavor.

To truly measure the cost of a healthcare encounter, organizations need all three of the above data sources. Next-generation business decision support tools facilitate this understanding by helping organizations more comprehensively define the true cost of the services they provide and those services’ impacts on patient outcomes. Ingesting all these data sources into a single source (such as a data operating system) creates an infrastructure that provides the most value – both upfront and long-term.

Competency #3: Analytic Transformation that Aligns Information and Identifies Populations

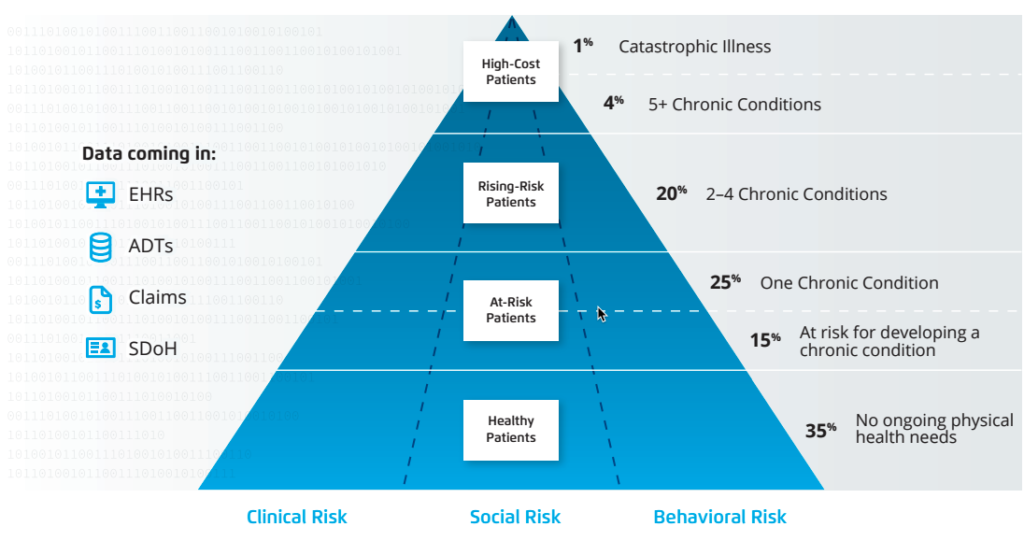

With the right governance structure and analytic backbone, clinically integrated entities are ready to identify appropriate contracts, stratified patient cohorts, and interventions. During this stage, various teams (as defined under the governance structure) will answer critical questions to drive interventions to the appropriate patients. By incorporating disparate data sources into a common structure, clinically integrated entities are building intelligence that allows them to succeed in appropriate financial and clinical transformation initiatives. Figure 3 shows how an operational vehicle (e.g., a clinical quality committee) can aggregate information and use an analytic tool to identify a population for a specific care management intervention.

Figure 3: An operational vehicle aligns information to identify populations for interventions

Competency #4: Payment Transformation that Drives Long-Term Sustainability

Entering at-risk contracts (not upside-only agreements) is necessary to achieve the appropriate financial revenues to sustain long-term value-based contracts. Organizations must seek a mix of contracts that appropriately align clinicians’ ability to impact select populations while meeting contractual obligations.

Some value-based contracts focus on leveraging an attributed patient population to reduce the total cost of care. The MSSP assigns attribution based on a combination of evaluation and management codes, which can unintentionally attribute patients to specialists or non- strategic entities (e.g., a neighboring physician whose tax identification number did not join the ACO).

While commercial payers and self-insured groups won’t be overly encouraged by the early results of Medicare’s Bundled Payment for Care Improvement Advanced program4, which demonstrated a net 2.5 percent increase in Medicare expenditures (after accounting for reconciliation payments) for predominantly specialty-focused episodes relative to a comparison group (see Figure 1); value-based contracts for specialists are increasingly available. These include episode-based bundle payments, risk-based convener for episode-based bundled payments, condition-based alternative payment models, and risk-bearing vendor arrangements for chronic conditions. The appropriate timing, prioritization, and mixture of approaches depends heavily on the local provider landscape, the degree of primary care accountability, and the readiness and resource availability for commercial payers to engage in specialty value transformation.

Competency #5: Care Transformation as a Key Intervention in Value-Based Contracts

Care transformation is a key intervention for internal cost savings in value-based contracts. While streamlining an approach to systemwide quality remains an important component of clinical integration, it can be a high-cost, high-effort undertaking. By optimizing care management programs, care transformation helps organizations reduce clinical variation and improve cost savings across the network.

Partners Healthcare a large, integrated healthcare delivery system, created its Integrated Care Management Program (iCMP) initially as a Medicare-specific intervention. Partners validated its model by examining Medicare patient data from 2012 to 2014, and reviewed overall total per beneficiary per month cost among other key metrics. The overall Medicare spending of patients enrolled in the Partners iCMP dropped by $101 PMPM (or $87 more than the cost decline for patients inside Partners’ ACO program), according to a 2017 study5.

Clinical variation reduction initiatives have also proven to be effective cost-reduction methods. For example, when a large integrated delivery system aimed to reduce unwanted clinical variation, it deployed an analytics platform to aggregate and analyze patient outcomes data. As a result, the organization reduced cost per patient by $2,401 and length of stay by more than eight days. These achievements translated to projected millions in savings in subsequent years.

Control the Levers—Identify Interventions Per Initiative and Scale

Intervention design typically occurs alongside payment and care transformation. Depending on the data, clinically integrated entities identify the value-based contract that aligns with their care transformation goals to impact costs with appropriate interventions. The next step is to determine which intervention to implement first. To do so, organizations must answer key questions about how various initiatives may impact specific value-based contracts:

- What are the cost drivers?

- Can the organization analyze variation of costs?

- What are the costs across the continuum?

- How much is driven by network management?

- How much is driven by clinical documentation?

Organizations then must decide which type of intervention to bring to market and when. This step requires a review of important characteristics making up contracts, with many of those characteristics remaining consistent across payer entities: Benchmark cost. Benchmarks are impacted by historical information of the clinicians inside the clinically integrated entity. To assist in evaluating how to approach network dynamics per benchmark, identify physicians’ TIN, the historical billing information per physician inside the entity, and whether attributed, will be retrospective versus prospective. Currency components. Currency components are areas of the contract that directly impact total potential to be earned. For example, some value-based contracts place PMPM dollars on meeting chronic care program utilization targets. This element complements an upside-only initiative that has a high opportunity to impact coordination costs and patient use of preferred health systems and clinicians.

Efficiency-based measure opportunities. Organizations need to negotiate or seek contracts with a favorable medical loss ratio, risk adjustment factor target, and efficiency- based measure opportunities. For example, after piloting a specific chronic care program, the organization may seek pharmacy management and utilization reviews as additional tools for cost reduction. The organization builds a more comprehensive complex care management program on top of the lessons they learned from the chronic care initiative to impact a new Medicaid-specific value-contract.

Organizations need to identify the intervention’s expected time to value, the financial impact, which patient populations it applies to, and how they will operationalize it. Next, health systems will place these interventions into an operational plan to address their ability for scale across multiple value-based contracts. This can help identify the appropriate time to move into a risk- threshold that optimally straddles both fee-for-value and fee-for-service payments.

The Continuing Journey to Better Quality at Lower Cost

The journey to value-base care is ongoing yet delivers increasingly better-quality care to patients at a lower cost along the way. Organizations can structure their journeys to value-based care by continually evaluating their performance in relation to their value-based care competencies. By understanding their current progress toward value-based contracting and factoring in local market needs, health systems can begin to identify strengths, as well as gaps, for effectively managing upcoming value-based care initiatives. Using a competency-based approach, and by leveraging purposeful interventions, organizations can create a framework for sustainable value-based contracting success.

References

- Guidance from CMS to state Medicaid Directors, page 4, Sept. 15, 2020 www.medicaid.gov

- 6th Annual Numerof State of Population Health Survey

- Medicare Shared Savings Program

- Medicare’s Bundled Payment for Care ImprovementAdvanced Program

- Bending The Spending Curve By Altering Care Delivery Patterns: The Role Of Care Management Within A Pioneer ACO, Health Affairs

This website stores data such as cookies to enable essential site functionality, as well as marketing, personalization, and analytics. By remaining on this website you indicate your consent. For more information please visit our Privacy Policy.